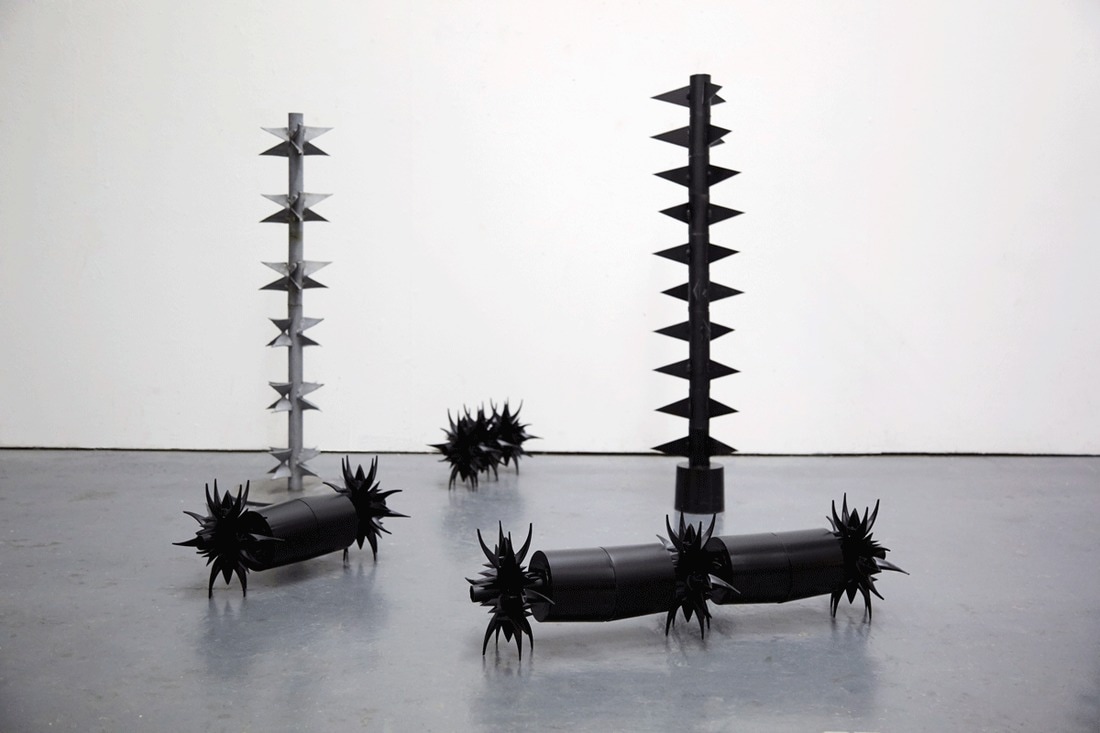

We Have the Weights, We Have the Measures / 1 June - 29 July 2017

Ewa Axelrad, Daniel de Paula, Marco Godoy, Ella Littwitz, Oscar Santillan

Ewa Axelrad, Daniel de Paula, Marco Godoy, Ella Littwitz, Oscar Santillan

|

|

Copperfield Gallery is pleased to present We have the weights, we have the measures, considering the relationship between the seemingly genteel pursuits of culture and learning and claims to geography.

Since the dawn of civilisation humans have attempted to delineate and lay claim to territory, but in more recent history such claims have extended beyond land and water to airspace, galactic space, even moons and planets. There is a certain implicit aggression in the act of claiming anything and yet history contains some surprising examples of the way in which this process is masked. An early example was the claim laid to what is now Brazil by the Portuguese: not on the threat of military strength but on the basis that they could map and navigate the land and surrounding waters. This proposes that knowing where you are in immediate terms is not enough — that governance requires a greater, quantifiable oversight backed by learning. Some of the more familiar cases of displacement of indigenous cultures in Australia, America, New Zealand and Africa echo the same principle, the same attempted justification that they needed ‘cultivating’. Through this lens the sculptures and installations draw attention to the ongoing trajectory of this kind of behaviour which is often hiding in plain sight. - - - - - - - - We have the weights, we have the measures A text by guest writer George Vasey I write this text in airports, and hotels as I fly between Berlin, Athens and Venice. From Documenta to the Biennial, I barely have to flash my passport. Since Article 50 was initiated this ease of access will no doubt be diminished. Of course, the EU’s trans-nationalism is only extended so far and while the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, other borders have been erected across Spain, Italy and Greece restricting the movement of people into Europe. Athens was a curious context for Documenta, which was typically epic. The leitmotif throughout the exhibition was a process of decolonising, foregrounding the voice of the colonised in place of their colonizers. It was a truly global exhibition that was fatally undermined by the cultural imperialism of a German institution using the poverty of Athens as a backdrop to talk about internationalism, given the uneasy relationship of Greece’s imposed financial austerity. It was bluntly summed up in a poster I saw at the Art School in Athens, “Documenta 14: FUCK OFF!” If the hardware of the modern Nation State is the border, the software is the cultural imaginary that naturalises entitlement to history and resources. Territory needs controlling and maintaining — both agriculturally and artistically. In what Eyal Weizman has called the “politics of verticality,” authority is exerted on land upwards and downwards through airspace and soil. If the border and the sky are militarised, it is archeology that is often instrumentalised and fictionalised to legitimise historical claims on space. In Berlin I walked past the partially rebuilt Stadtschloss, a good example of how architecture is used to re-wire the software of a nation state. 28 years after the fall of the Wall and 50 years after demolition of the original Stadtschloss, the reconstructed version is due to (re)open in 2018. It was badly damaged during Allied bombing in the 2nd World War, and the occupying GDR bulldozed the original palace and built the Palast der Republik in 1973, which — deemed politically redundant in a newly unified country — was also knocked down in 2008. The site has become an architectural palimpsest, with each successive regime erasing the previous administration, the architecture becoming a site of a contested claim to territory. If the Wall controlled the East’s territory spatially, the Palast der Republik maintained an other type of claim to its ownership. The victor of war is also the author of history, with their authority written through the architecture that they build (and knock down), the art they make and the narratives they extol and erase. One can see the Stadtschloss, as a manifestation of neo-liberalism as the defining economic model, articulated through an architecture of historical dementia. Facia and fiction coalesce, and while all history becomes readily available, the recent past quickly becomes forgotten. A building can camouflage and memorialise, speak of histories or erase them. Authority is exercised temporally and spatially. The museum, the pop song, archeology and architecture can all be weaponised and fictionalised to suggest genealogies and entitlements on land. As I travel through Europe I think about all the stateless people. The undocumented migrants hawking goods on San Marco Square, the refugees that line the streets of Athens — people with no claim to space and no voice in which to amplify their own narratives. How do their histories get told and remembered, inscribed on the topography of the cities they inhabit? The passport in my pocket, which enables visa-less access to all these countries, is a privilege maintained by structural (and physical) violence — one that is persistently controlled and maintained by the hardware and software of the modern state. |