KaplanKaplan / 2 February - 18 March 2023

Giuseppe Abate, Larry Achiampong, Emmanuel Awuni, Ada M. Patterson, Rebeca Romero, Oscar Santillán, Laila Tara H

Giuseppe Abate, Larry Achiampong, Emmanuel Awuni, Ada M. Patterson, Rebeca Romero, Oscar Santillán, Laila Tara H

|

|

Questioning the many forms of the so called "Western Gaze", this exhibition celebrates the critical potential of figuration in contemporary art practice with works that are content rich, exploring new ideas or using unusual materials and practices. The term Western Gaze has come to extend to many things but ultimately it refers to the Eurocentric, hegemonic bias that has permeated not just our ways of representing but also our ways of describing and even of seeing.

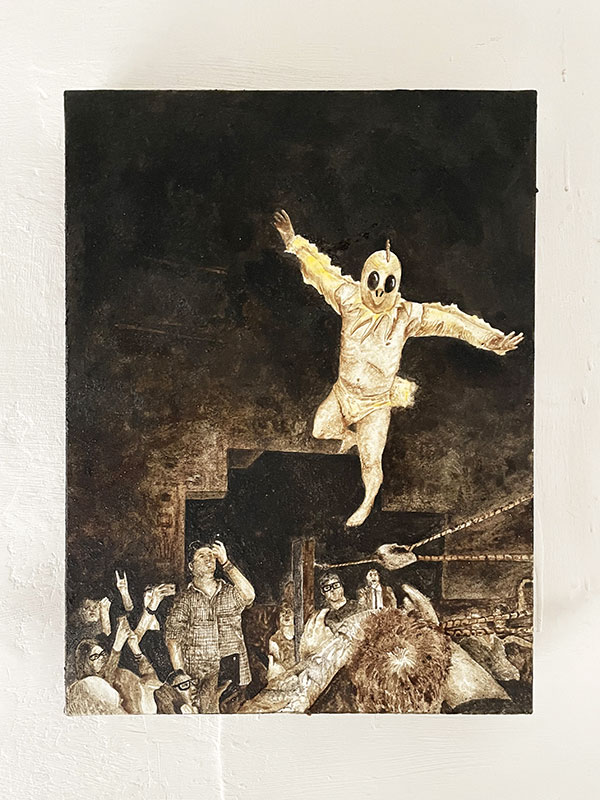

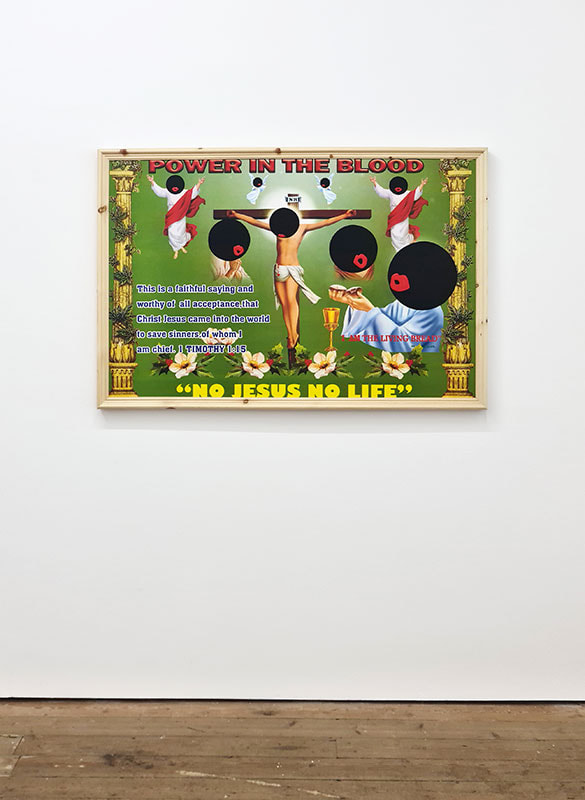

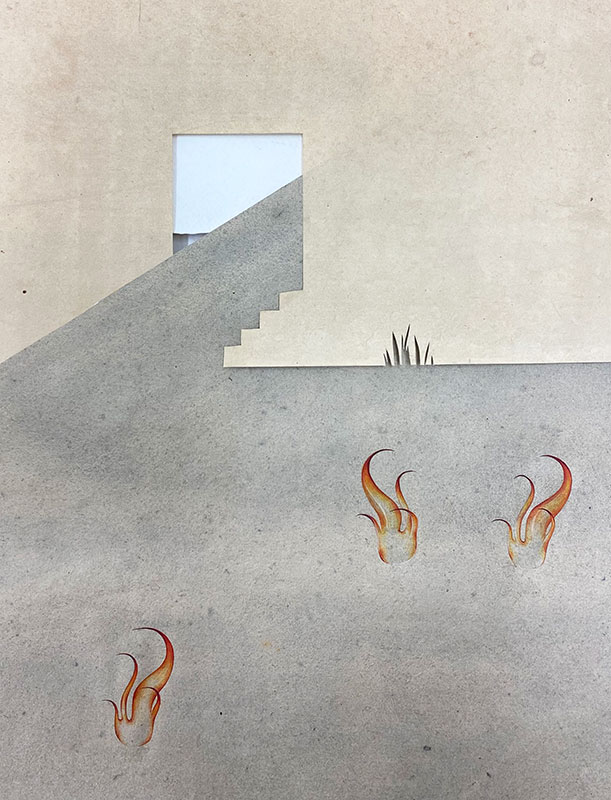

Oscar Santillán’s research has found that one of the major differences between the mindset of Western colonizers and the Indigenous communities in the Andes region of his ancestry, were the divergent ways in which these two worlds related to reality itself. The colonisers attempted to classify everything in order to define and commodify it which was often totally at odds with vital local concepts. For example, often, where the colonizers saw ‘land to be owned’, the inhabitants of the Andes saw sentient entities, which nowadays many still call ‘earth beings’. Santillán’s ‘Antimundo’ paintings set out to frustrate normative categories and representations that have allowed visual definitions of plants animals and minerals. The methods used by the artist in order to generate this ambiguity include an image generation programme trained with diverse source material including many images from colonial archives, and a digitally 3D rendering the resulting imagery. Able to approach his preprepared subject matter as if upon discovery Santillán translates the resulting digital imagery into the very medium traditionally used for such representations, oil painting. The Antimundo images are in dialogue but also in tension with the normativity of Western narratives and ways of seeing. In particular the inability to define precisely what is depicted in these hybrid images frustrates any commercial interests in the actual subjects of these paintings from resources to livestock. Put simply, if you can't define it, you can't sell it. Ada M. Patterson translates underpaintings into printed textile Kanga. While the Kanga tradition is one of intimate messaging between individuals through the gifting of worn garments, Patterson has developed her own strategy for sharing similarly personal messages within this tradition, but with a global urgency. Her Kanga have mostly focused on the grief and turbulence of climate change in her native Barbados and beyond. More recently, her Kanga have become a way of honouring different kinds of life being lived with crisis. Against the overload of news networks, social media and advertising that describe the world for us today and influence our priorities following imperial principles and tactics, Patterson’s subtle communicative process through garments considers the ways we might redistribute grief in a world where some lives are more expendable than others. Emmanuel Awuni has experimented with various painting traditions for years, but what has recently crystallised is a new body of work that comes directly from the language of painting into something else. Artifact packing foam makes up an almost pop blue background and housed within deep tray frames the combination stands for the thousands of high specification packing crates that cradle and confine the remains of thousands of cultures in museum storage facilities around the world -- predominantly the Western world in the wake of centuries of empire and colonial policy. A careful selection of both cheap found objects and painstakingly made ceramics are inserted into the foam, following minimal painterly compositions that read as such from a frontal perspective. These need exploration however, as further perspectives reveal details on the frames, in the sides of the objects and so on. Through multiple references and symbols both on the frames and the objects themselves further questions are raised about the status of artifacts and remains from around the world when mediated by museum collections. Awuni is not simply replicating museum artifacts, he is driven by and reclaiming the spirit of ancestral practice in his own contemporary context. Working with materials derived from the waste of poultry processing in the food industry such as bones, blood, eggshells and others, Giuseppe Abate has made paintings that reflect on the society of consumption and its visual representation. “While working in London I was attracted by the number of chicken shop signs I saw and by how many times the word “chicken” appeared on billboards. Through analysis of advertisements, expressions, books, movies, cartoons and chicken shop fights videos, I realized that chicken represents much more than an animal species in Western culture”. Black Burned Bones, Eggshell Complexion, Livorno’s White and Sienna Rooster Blood are the four pigments used in the paintings -- powders developed by the artist from organic chicken waste. We find them in the series of egg tempera on canvas The Cockpit, where images of violence set in the chicken shops of London are juxtaposed with copies of portraits of champion roosters winning in cockfights of the mid-nineteenth century. These contrasting visions of masculinity, violence, food and consumption are framed by a forest scene painted directly on the gallery walls in egg tempera made with the Black Burned Bones pigment and refers to the fashion for landscape art in wall painting and interior tapestry in C17th and C19th England. Chickens, chicks, hens and roosters scamper free there in an exotic landscape, confined in an artistic genre inextricably linked to imperialistic practices and ideologies. Larry Achiampong’s painting Power in the Blood (2022) considers how belief systems within the diaspora are inflected by colonial histories. In particular, it unpacks the relationship with Christian imperialism and its impact on his ancestral tribe, the Ashanti. Under enigmatic phrase that gives the work its title, this type of super kitsch board mounted poster can only be found in parts of the world were colonisation occurred with missionary work — from Ghana to the Philippines. The incongruity of a chalk white Jesus with his apparently middle eastern origins is widely questionable, but in the context of countries that have been repressed by white western nations the apparent perpetuation of these images by congregation of color becomes more unsettling. Painstakingly sourced and imported from Ghana, the poster is typical, with its plethora of graphic and immediate imagery that draws on a pastiche of the language of past advertising styles and, in turn, so does Achiampong’s response. While the Golliwog or minstrel show character is an uncomfortably recognisable icon of Britain and America's colonial past, the immediacy of this image when reduced here to an internet style avatar, belies its complex and often obscured history. Other more subtle painted edits and editions amplify the way in which these works question and take ownership of these problematic legacies. Using Machine Learning programmes computers have the ability to harness massive amounts of data and use their learned intelligence to make optimal decisions and discoveries in fractions of the time that it would take humans. For a new series of paintings Rebeca Romero fed an algorithm with written descriptions of ancient artefacts, taken from Western museum labels. In feeding this neural network she asking it to imagine the visual appearance of further artifacts based on that material -- those that might have been lost, those that could have been, those that can stand in for what colonial incursions ended and then re-contextualized. The finished images are rendered as paintings in a nod to early colonial painted records of such discoveries where their western classifications began. As an Anglo-born Iranian, Laila Tara H. deconstructs the aesthetic framework of the Persian miniature tradition, hybridising it with that of its European counterparts to form her own visual language, paying particular attention to the examples where these traditions met and mixed. Her works unpack her lived experiences often in relation to gender roles and familial structures, connecting to the similarities and differences between the different cultures she has experienced. Iran and Europe, but particularly England have not existed in a vacuum but are in many ways inextricably linked – not least politically. Despite having distinct visual and cultural traditions the two have affected one another with their gaze. Past and present notions of female desirability have often played a part in Tara H’s abstracted presentations of body parts, noses, faces, considering the effects that historical and present European and Iranian interactions have had on one another and by extension, on herself. Runs Wed - Sat, 12 - 6pm until 18 March 2023 Artists CV's are available on request |